One winter evening in 1786 on the outskirts of Vienna in a small wooden house the blind old man was dying, he was a former chef of Countess Thun. It was not even a house, more like a dilapidated lodge standing in the back of the garden. The garden was littered with rotten branches, whipped by the wind. At the each step the branches crackled, and then the watchdog started to grumble quietly in his booth. He was also dying from an old age as his master, and could not bark.

Several years ago, the chef was blinded by the heat of the stoves (furnaces). The manager of the Countess let him stay ever since in the lodge and provided from time to time a few florins.

He had an eighteen year old daughter Mary, who lived with him. The small lodge had only the bed, the rickety (lame) chairs, the rough table, the crockery full of cracks, and finally, the harpsichord – the only valuable of Mary.

The harpsichord was so old that its strings were singing long and quietly in response to all emerging sounds around. The chef jokingly called the harpsichord as the guardian of the place. No one could enter the house without the harpsichord’s greeting with its trembling old clatter.

When Mary washed her dying father and dressed him in a cold clean shirt, the old man said:

“I never liked the priests and monks. I shouldn’t call the confessor, however I need to clear my conscience before the death.”

“What shall I do?” asked Mary with concern.

“Go outside,” said the old man, “and ask the very first passer to come and hear my confession. There shall be no refusal.”

“But our street looks so deserted …” whispered Mary, put on a scarf and went out.

She ran through the garden, barely opened the rusty gate and stopped. The street was empty.

Mary had been waiting and listening for a long time. At last, she thought she heard someone passing along the hedge and humming. She took a few steps towards the person. Running into him she screamed. The man stopped:

“Who’s there?”

Mary grabbed his hand and with a shaking voice conveyed the request of her father.

“Very well,” said the man gently. “Although I am not a priest, it shouldn’t matter. Let’s go.”

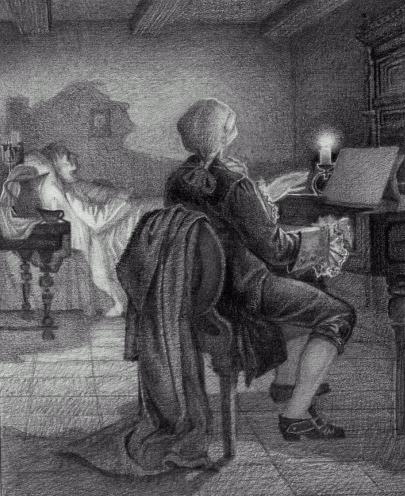

They entered the house. With the help of candle lights Mary saw a small lean man. He dropped his wet raincoat on the chair. He was dressed plainly but with elegance. The fire light glistened on his black vest, the crystal buttons and lace jabot.

He was still very young, this stranger. Trippingly he shook his head, adjusted his powdered wig, quickly pulled up a stool to the bed, sat and leaning closer piercingly looked into the face of the dying man.

“Please speak!” he said. “Perhaps with the power given to me not by God, but by art, which I serve, I could ease your last moments, and lift the weight off your mind.”

“I worked all my life until getting blind – the old man whispered and pulled the stranger’s hand closer to him. – And those who work don’t have a time to sin. When my wife became ill with consumption – her name was Martha – and the doctor prescribed her various expensive drugs, and ordered to feed her with cream and wine berries and drink hot red wine, I stole from the Countess Thun little golden plate, broke it into pieces and sold. It is hard for me now to reflect on it and hide from my daughter. I taught her not to touch a speck of dust from someone else’s table.”

“Were any of the Countess servants punished for that?” Asked the stranger.

“I swear, sir, no,” said the old man, and wept.

“If only I knew that the gold will not help my poor Martha, I would have never done it!”

“What is your name?” Asked the stranger.

“Johann Meyer, sir.”

“Dear Johann Meyer,” the man said, and put his hand on the old man’s blind eyes. “You are innocent. What you committed is not a sin, but on the contrary, can be credited to you as an act of love.”

“Amen!” The old man whispered.

“Amen!” Repeated the stranger. “Now tell me your last will.”

“I want someone to take care of Mary.”

“I’ll do it. What else you wish?”

Then the old man suddenly smiled and said aloud:

“I would like to see Martha again same as in her youth. I want to see the Sun and this old garden when it blossoms in the spring. I know it is not possible sir. Do not be angry with me for this foolishness. The disease must have taken its toll on me.”

“Very well,” said the stranger, and stood up. “Very well,” he repeated again, approached the harpsichord, and sat on a chair next to it.

“Very well!” He said loudly for the third time, and suddenly the swift sound broke the lodge, as if the hundreds of crystal beads got scattered on the floor.

“Listen,” said the stranger. “Listen and watch.”

He started to play. Mary could never forget the face of the stranger when he pressed the first key. His forehead became unusually pale and the darkened eyes reflected the candle lights.

The harpsichord was singing in full voice for the first time in many years. He filled with sounds not only the lodge, but the entire garden. Old dog crawled out of the booth and sat tilting his head on one side, wary, slowly waving his tail. The wet snow began to fall, but the dog just shook his ears.

“I see, sir!” Exclaimed the old man propping himself up in bed. “I can see the day when I met Martha and she became so shy that broke the jug with milk. It was winter day in the mountains. The sky stood clear like the blue glass, and Martha laughed. Laughed!”

He repeated, listening to the strings ringing. The stranger played looking into the black window.

“And now,” he asked, “do you see anything?”

The old man was silent.

“Don’t you see,” quickly said the stranger still playing, “that the night from black turned into blue, then azure, and warm light is falling from somewhere above, and the old branches of your trees bloom with white flowers. I think those are apple flowers though from this room they look like the big tulips. Don’t you see how the first ray of sunshine touched the stone wall, heated it, and the steam is rising already. It must be the moss drying up, filled with melted snow. The sky is rising higher and higher, turning into deep blue, ever more magnificent and flocks of birds already heading North over our old Vienna.”

“Yes! I see it all!” The old man cried.

The pedal quietly creaked and the harpsichord continued its solemn song, as if it wasn’t the instrument but a hundred elated voices performing.

“No, sir,” said Mary to stranger, “the flowers don’t look like tulips at all. Those are the apple trees which blossomed in a single night.”

“Yes,” answered the stranger, “those are the apple trees, but they have very large petals.”

“Open the window, Mary!”, requested the old man.

She did. Cold air rushed into the room. The man was playing very softly and slowly.

The old man fell on his pillows, greedily breathing and fumbling around the blanket with his hands. Mary rushed to him. The stranger stopped playing. He sat at the harpsichord, unmoved as if enchanted by his own music.

Mary screamed. The stranger raised and walked over to the bed. The old man said, breathlessly:

“I saw it all so clearly, like many years ago. But I don’t want to die without knowing … name. Your name!”

“My name is Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart,” replied the stranger.

Mary stepped back from the bed and almost touching the floor with her knee, bowed low before the great musician.

When she straightened up, the old man was dead. The dawn was flaring up outside the windows and within its light the garden engulfed with the flowers of wet snow stood still.

A short story “The Old Cook” by Konstantin Paustovsky